“Hi, I went to your web sight and did not find information about your bored. If sum one is on this list, please let me know.”

I’ve attended my share of bored meetings, in the truest sense of the word, but the errors in this listserv post point to a separate problem—words that sound alike but mean different things and are spelled differently. We’ve had customers email us to complain about “sellphone charges,” ask if it’s “all rite too send cash,” or question what “cited people” think, adding, “if only they could see it threw my eyes.”

Homophone slips are ubiquitous: I remember how embarrassed I felt when a published review on a book I had edited flagged my misuse of “peak” for “pique.” I was supposed to know better because I was getting paid to know better. But the likelihood of homophone abuse goes up, in my experience, when speech is the primary mode of reading and writing. In fact, ahem, if you’re reading this blog with JAWS, you may wonder what crime has been committed.

There are three possible trip-ups for writers in this arena:

- Homonyms: Two or more words that are spelled the same and sound the same but mean something different: The ROSE bush ROSE up 12 feet high.

- Homophones: Two or more words that sound the same, but are spelled differently, and mean different things: The BEAR was BARE.

- Homographs: Two or more words that are spelled the same but sound different and mean different things: The striped BASS played the BASS guitar.

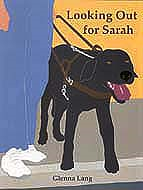

Lorraine Rovig, who works at the National Federation of the Blind, suggested that NBP publish a list of homophones in braille. What better way to learn about words that sound alike but are spelled differently than by touch? Sound alone compounds the problem. We added some other cool stuff and called it A Writer’s Companion.

Is this a shameless plug for the book? It is. We all knead two no how too rite better oar look foolish. Blind people face many obstacles but writing a professional cover letter or a college essay need not be one of them. This email from Grace Scullin was spotless: “I love A Writer’s Companion! If it had only helped me with there / their / they’re, I would have been satisfied.”

Read a review of A Writer’s Companion from Matilda Ziegler Magazine for the Blind.